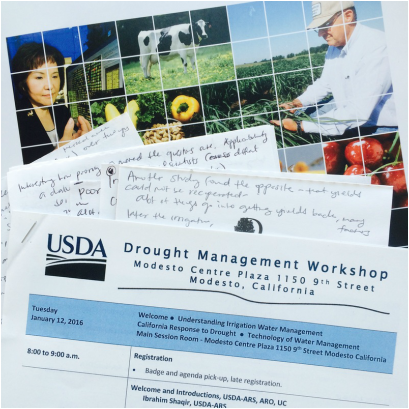

Using Current Conditions & a Drought Conference to Ponder the "Merit-Basis" for Policy Change & Aid1/30/2016 Two weeks ago a big storm dumped a lot of rain and caused flash floods across the Bay Area and Sacramento Valley. My personal frustrations with the storm’s inconveniences became apparent quickly, which only frustrated me more (why get frustrated by precipitation, when we need it?). I had to pay nine bucks to use visitor parking after a long and rainy early morning drive from Oakland to Davis. Had to acknowledge that choosing to not wear rain pants was a mistake (jeans soaked). The check engine light came on after I passed through a very large “puddle”. The dog was going completely bezerk in the car——panting so hard from anxiety that he fogged up the windows even with the defroster on. Jones, can you please stop breathing? And while you’re at it, make this rain stop, too? Whoa, wait! Nevermind about that last one! I don’t want the rain to stop——what am I thinking?! The ugly truth is that even with the knowledge I have about the status of the drought and my relatively high tolerance for lots of precipitation, my humanness makes me short-sighted, forgetful, and prone to discounting problems when they seem temporarily resolved. On the drive home, I began to question my judgment on the storm’s intensity. On a scale, how stormy was that storm compared to others I’ve experienced in Northern California over the years? Is the rain and snow we’re getting helping? How much? There are a lot of great sources to help answer these questions. California’s Climate Tracker and NOAA both have data that goes back as far as the late 1800s. (It's worth giving a shout-out to the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service's site too; among many other things, it compares current precip data to historical averages at specific sites across the country). The California Climate Tracker shows that in December 2015, the state was at 106% of normal precipitation based on historical averages. The precipitation was not evenly spread across the state. The Bay Area and Sacramento Valley were at 50-70% of normal and the foothills and Northern Sierra were at 110-135% of normal, for example (the higher figures in the Sierra is a good thing——we need snow more than we need rain). NOAA provides a sense of variability and relative severity by ranking time periods in terms of their warmth, level of precipitation, and so on. Even though it felt like a lot of rain at the time, this past December was only the 40th wettest (4.47 inches). December 2014, on the other hand, was the 17th wettest (over 6 inches of rain on average). The problem last winter, though, was that December was also the 7th warmest, so we had limited snowfall. Moreover, the state received less than an inch of precipitation in January 2015 and less than 3 inches in February. Although we’ve had a wetter January this year, rain and snow events seem to be dissipating quickly and the temperatures are climbing. There are visible consequences already. So the answer to whether the precipitation the state has received this water year has been helpful seems to be sort of. Of course, it has helped——anything helps!——but the precipitation thus far has not made a huge dent on the drought problem, at least relative to water consumed. Reservoirs are a good way to get the gist of this. Right now, they’re still very low. As of yesterday, all reservoirs are under their total capacity by 50% or more and well below their historical averages. Folsom Lake is at 42% capacity; its historical average for today is 81%. Lake Shasta is at 48%; its historical average for today is 78%. These trends persist across storage systems in California. One reason the rain hasn’t helped fill reservoirs is the length of the on-going drought. Instead of producing run-off, the rainwater seeps into the parched ground. Snowpack usually helps fill reservoirs through the spring and summer, but that depends on how fast the snow is evaporated and melted as temperatures warm up. These facts reiterate what I learned two weeks ago at a Drought Management Conference in Modesto, hosted by the USDA in collaboration with various departments at UC Davis. Researchers and stakeholders in agriculture from California, Israel, and Australia were invited to present their findings and practices to other interested researchers and stakeholders. Why would a political scientist go to such an event? Well I went because my colleague and I are trying to figure out how governments make policy choices and distributive decisions when water resources get tight. We have reasons to believe that these decisions reflect political motivations in some situations. Yet they might also——and likely do——reflect objectives to sustain agriculture, farmer livelihoods, and the environment during these periods. They probably also reflect the scientific uncertainty in how to go about doing these things. To assess the motives that lurk within decision-making, it's important for us to understand what we call the “merit-based” motives that actors in government may take into consideration when changing policy and making investments. Below, I use some of what I learned at the Conference to reflect on what might constitute merit. One merit-based angle governments might consider when investing in solutions and relief to drought is drought severity. In other words, political actors might ask themselves whether and where the drought is bad enough that it necessitates policy change and/or aid. A representative from the California Department of Water Resources explained that the main precipitation window in California is from December 1st through mid-February. Although this has been a rainy winter compared to the last few, we are--as I said earlier--falling short of expectations. And even if additional storms pass through the state due to El Niño this spring, we need well above average (like 200-250+ percent above average) to be a more comfortable with our water situation. The lack of rain and snowfall are not the only problem, however. The world is getting hotter in general, so this El Niño has brought with it characteristics never observed before: cycles of intense storms and then periods of dry and warm conditions. The speaker drove home that storms are not created equal. The degree to which a storm relieves drought is a function of the storm’s timing, flux, duration, direction, freezing elevation, and spatial extent (where the storm travels). The also speaker noted, pretty gravely, that some site records in the Sierra show that the average temperature during winter months was 32.1 degrees in 2014. The problem is not just maintaining snowpack, but getting it at all. Another thing decision-makers might think about when making policy changes or distributive choices is where food crops are grown, and what they require to be grown there. In other words, whether the economic, social, and environmental benefits are such that it makes sense to maintain certain types of production in particular locations. How much water is needed to produce crops——and more importantly, maximize yields——is one element that might inform this call. Yet it became clear at the Conference (and news to me) that how much water is needed to maximize yields is not well understood. Farmers rely on estimates of crop evapotranspiration, or the water loss produced by soil evaporation and crop transpiration (i.e., tree breath), in order to determine the amount of water a crop needs. Estimating crop evapotranspiration is challenging though. The standard estimates require data on temperature, precipitation, and crop characteristics. More advanced estimates would include measures of crop stress such as the level of soil salinity. Researchers from the Department of Land, Air, and Water Resources at UC Davis and from the Golan Research Institute in Israel explained that almost all of these factors can change within a single plot. Whether the individual plant is the north or south side, shaded by tree canopy, or on a slope are just a few elements that impact crop evapotranspiration. Put simply, figuring out the minimum amount of water needed to produce the most food not all that straightforward.

Although not exactly framed in these terms at the Conference, crop resilience to drought stress seems like a factor that might determine merit. The capacity of species to withstand and bounce back from dry conditions varies dramatically, and is a particularly important consideration in food crops like orchards that have high start-up costs and that are more of less 'permanent' once planted. A surprise to me, research shows that almond trees tend to be more resilient than other nut tree types. A recent study found that almond trees exposed to dry-farming (meaning they receive no irrigation) in Kern and Merced counties lost their canopy early in the season and had lower yields. Yet not only did these trees survive the water scarcity, they also rebounded and produced normal yields within two years after returning to a normal irrigation schedule. Pistachio and walnut trees are not as resilient to stress. Presenters discussed mixed results on adaptability, and suggested that walnut trees seem to have the most trouble recuperating after deficit irrigation. It is worth pondering whether crops that can survive and then recover from drought are the most deserving of government support and/or continued to access to water, or whether crops that struggle through it are most deserving. One could argue that farmers growing less resilient crops have the greatest needs for stable water allocations or government funds for innovative technology because farmers that produce more resilient crops can fallow their land and the crop or orchard is more likely to recover. One could also argue, however, that farmers growing less adaptable species should cease growing them in a region with increasingly warmer and drier conditions. Water allocations that reflect a strategy to preserve the most resilient species would ultimately consume less water and leave more water for other purposes such as environmental flows, since these crops and orchards have an easier time maintaining production even when exposed to deficit irrigation. Of course, figuring out which farmers to support or how to create incentives to change how their water use is not that simple. The market value of the crop produced, for example, might play a central role in assessing which farmers need assistance. High-value crops like deciduous nut trees——resilient or not——can often ‘survive’ drought because they create enough profits to cover the cost digging wells in water regimes like California's or to pay for temporary water rights in regimes like Australia's. Farmers growing these crops on a large scale may not need government support at all, although they (and other water users) might benefit if they implement efficient irrigation technology. Another factor that certainly impacts how governments choose to allocate water or funds are prior decisions. Governments seeking to maximize water efficiency are often constrained by the operational rules and infrastructure established in the past. Finally, what the government can offer farmers and whether what they offer reflects merit-based motivations depend on the innovation and solutions available. Agricultural innovations and solutions to water scarcity were the main focus of the Conference (and will be discussed in more detail in a separate blog). Some of these solutions are carried out on the farm. Researchers and extensionists discussed various strategies to maximize yields and protect orchards exposed to deficit irrigation. Reducing irrigation early in the season and maximizing it during critical growth periods (e.g., when the kernel of the pistachio is filling), de-branching trees, and thinning fruit to attain commercial size in those that remain are examples of such strategies. Other non-farm strategies——and ones that require government involvement at some level——include updating canal and reservoir infrastructure, and using recycled or desalinated water for irrigation. Although promising and with some success in Israel, new research and experience has shown that applying recycled and desalinated water to crops can be tricky and has some negative consequences. It seems that we have only a partial understanding on the conditions in which these sources are used and the limits of their use. The uncertainty that comes from innovation makes it even more difficult for governments to make merit-based policy changes or choose solutions to invest in.

0 Comments

What the Past Has to Say: Summarizing The West Without Water (Ingram and Malamud-Roam 2013)12/14/2015  “The North American West has been ideal for human settlement in last 150 yrs.” (47) “We are building a great empire on the edge of the desert… to maintain our mastery over the desert”. Chairman of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California in 1931 “Today’s society in the West resembles the Ancestoral Pueblo of the twelfth century—--both living beyond their means”. (206) I recently finished The West Without Water: What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tell us About Tomorrow by B. Lynn Ingram and Frances Malamud-Roam (2013). It was super informative and surprisingly easy to read (a significant accomplishment since one the most challenging tasks in science is translating it into something the public and non-scientist can consume). The purpose of the book is to use paleoclimatology (the study of past climates over earth’s history) and other ‘past-oriented ologies', like anthropology, to explain what we might expect of the climate and its impacts on living in the West in the future. In this blog, I summarize some of the key points and the narrative that spans the 220 pages. What’s here is already a lot of information, so I’m forgoing discussing the natural causes of climate changes and encourage folks to read the book to learn more. All of the information I present below is drawn from Ingram and Malamud-Roam (2013). I provide page numbers when I use a direct quote. In the final two paragraphs, I comment briefly on what the book made me think about——these are my reflections and should not be attributed to the authors. To start, the authors define ‘climate’ as opposed to ‘weather’. These terms are often used interchangeably, but really shouldn’t be. Climate “refers to the statistical description of ‘weather’ over a given period of time and for a given region, including the weather extremes” (2). This is especially important to mention concerning the weather we’ve been having in Northern California: while rain and snow help reduce drought severity (that is, if it doesn’t come all at once), the long-term weather pattern shows that the region will be be hotter and drier, and that we can expect bigger and wetter storms that lead to flooding. Before diving into what we can expect in the future, I want to provide a few details of the authors’ scientific approach to constructing these expectations and some of what they find. The authors use the recent climate and weather phenomena, i.e., over the last 150 years, as well the climate and weather phenomena over the last twenty millennia and earlier, to determine whether the past contains trends and patterns that can be used to predict the future. The more recent stuff is important because it is the window in which we can look at the effects of anthropogenic, modern human activity on the climate and resources like water. The older stuff is important because it exposes earth’s natural cycles when humans weren’t so modern——and when there weren’t so many of us. To analyze the older and more long-term trends, scientists learn from data in sediments, trees, vegetation communities, and wildfires. Sediments, deposited in lakes, basins, oceans, and estuaries on earth’s surface, can span millennia. Certain species of tree also contain a millennia’s worth of information: some Bristlecone Pine in the White Mountains near Death Valley, for example, are over 4,500 years old. Their tree rings can be used to analyze the length of wet and dry periods, where tight rings indicate limited rainfall. Ancient tree stumps submerged in closed-basin alpine lakes are also reflections of the past: their mere existence tells that the region was much drier and for long periods of time. By examining vegetation communities in the Sierra Nevada, or whether certain types of trees are found growing separately or together, scientists can infer whether the springs and summers were dry or wet, warm or cool. Ingram and Malamud-Roam (2013) discuss the findings from these various analyses to triangulate evidence on climate and water availability patterns. I discuss some findings here, beginning with quite a long time ago. For the last two million years, earth has traversed between glacial and interglacial periods. The last “glacial maximum” was approximately 20,000 years ago; at this time, ice sheets were likely tall enough——two miles thick in some areas of North America——to interfere with earth’s atmosphere. When the earth began to warm, enormous lakes formed across the “Great Basin”, an area that extends across California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Oregon. The Holocene period, one of global warming, began when these large lakes started to shrink approximately 15,000 years ago and has persisted through today. Humans first began arriving in the West soon after the start of the Holocene. These early societies were highly mobile, matching the ebb and flow of wet and dry periods in the West. Several periods of severe drought and flooding——much more severe than modern Westerners know it——occurred during the Holocene. One mega-drought, spanning centuries, occurred mid-Holocene. Before discussing the other prolonged droughts, it is worth noting that before their arrival came a wetter “Neoglacial” period, which clearly affected lifestyles of early human populations living on the coast and in the West more broadly. In the San Francisco Bay area, for example, the Olhone people built and lived on ‘mounds’ composed of shellfish remains, adding to their height as water levels from floods increased. Some of the largest mounds in this period were 500 feet long and 30 feet high. The Neoglacial era gave way to drier conditions. Two prolonged droughts occurred 12-1100 years ago across the West——droughts of this magnitude are likely to occur again in the future. Sediments show that the salinity of marsh in the delta and bay were 40 percent above today’s level for over a thousand years, implying low levels of freshwater and a long dryspell. Ancient lakes dried completely (some returned during subsequent wetter periods). Entire civilizations based in Arizona and New Mexico collapsed within a short period of time due to the droughts. Anthropologic evidence shows that these societies experienced malnutrition, starvation, disease, possibly warfare, and were forced to flee. Groups living in slightly more hospitable environments like in southwestern Colorado and Utah began building dams and canals to capture and move water for agriculture, but these were soon abandoned. Coastal populations faired a bit better but still suffered, and delta groups moved to the mountains. The authors point out that this intense warming period was a global phenomena. In higher latitudes, populations flourished from the increased warmth. Now for the short-term, starting with water usage and depletion. Modern human activity in the West accelerated during the Gold Rush, so as recently as the mid-1800s. The hydraulic era began in the early 1900s as the population grew and water needs increased. The surface area of the now arid Tulare Lake was almost 700 square miles at this time, making it the largest freshwater lake west of the Great Lakes. It was diverted for agriculture and fluctuated in size until the 1930s-1950s when occasional flooding prompted the damming of the remaining tributary rivers. Owen’s lake had a similar fate, diverted to Los Angeles for drinking, agriculture, pools, and lawns. With lakes and groundwater resources drying up and after a Dust Bowl-type drought in southern California, the aqueduct ‘solution’ emerged. Propaganda such as the 1931 film “Thirst” encouraged voters to approve a bond to build an aqueduct over 240 miles long from the Colorado River to Los Angeles. (I highly recommend watching the film——there’s a lot to reflect on). Decades later, the California aqueduct was built, linking the Bay Delta to Southern California. Both state and federal state governments invested in large-scale hydrology projects; there are now over 1,500 dams in this state alone. It took less than a century for all of the water in the West to be engineered. Such rapid human intervention has had far-reaching consequences on the West’s ecology——much of which we rely on to survive here. Here’s a very short list. After 1850 when livestock were introduced, there was a six-fold increase in dust in the southwest. While the dust declined when the government passed the Taylor Grazing Act, it continues to increase as the human population expands. Dust has far-reaching negative effects: it darkens the surface of snow, causing it to melt faster and leave less snow for summer months. During the dry period before the Colorado aqueduct was built, the ground sank by 100 feet in some places due to groundwater depletion (“Thirst” reminds voters of this fact, but ironically the sinking is used to justify maintaining the population in southern California rather than reduce it). Continued groundwater depletion has led some areas in the valley to exist well below sea level today, leaving many residents extremely vulnerable to floods. There were 4-5 million acres of wetlands in the Central Valley in the early 20th century and one tenth of that area remains. The disappearance of wetlands and water diversion has drastically changed the ecology of California and its native and migratory species. Over three fourths of the native freshwater fish population in California, for example, are extinct or endangered. While water resources are tapped and reduced, the climate in the region continues to warm. The region has experienced two recent severe droughts plus the one we’re in currently. The 1976-1977 drought was severe in the very short-term, extending across the West into Montana. The 1987-1992 drought was longer and led to water use reductions of 75 percent for agriculture in California. River flow was so low that it decreased hydropower dramatically. Instances of these extensive droughts are expected to increase as the climate gets hotter and drier and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions continue to be released into the atmosphere. Nine of the ten warmest years occurred since 2000, and we’re breaking records every year. Climate models predict that by 2100, the snowpack could shrink by at least 40 percent. Although modern civilization in the West has had fewer instances of too much water than it has of too little, there have been several deluges and scientists predict that there are more to come relatively soon. As paleoclimatology shows, drought conditions are punctuated with severe flooding. The worst flood in the modern period occurred in Northern California during 1861-1862, and after very dry years. Precipitation was so great that Napa and most of the Sacramento Valley were blanketed in six inches of snow. The floods that resulted were so severe that they submerged the entire Sacramento Valley in more than 10 feet of water for months. Thousands of people died and hundreds of thousands of cattle drowned in the flood, ending California’s cattle-based ranchero society. The Gold Rush era was partly to blame for the severity of the floods: over 1 billion cubic feet of mining debris had infiltrated the river system. We have had two major recent flooding events. Both the 1997-1998 and 1982-1983 floods were the result of EL Niños. Together and worldwide, they caused 120 billion dollars in damages and almost 25,000 deaths due to floods, droughts, and wildfires. (Although I don’t get into it in this post, El Niños cause drought and flood simultaneously across the globe. While we’re preparing for heavy precipitation in California this season, for example, South Africa and Ethiopia are going through some of the worst droughts they have had in decades). Scientists propose, however, that we have yet to experience the mega-floods that have been part of the region’s pattern——not even the flood of the 1860s compares. Mega-floods, which dump enough water to revive ancient lakes in places as dry as the Mojave Desert, have normally occurred every 200 years. It has been more than 400 years since the last one, and evidence is building that the West is overdue.

Evidently, climate variability in the West should not be taken lightly. Part of the reason it should not be taken lightly is because modern activity and the release of GHG emissions have decreased our confidence in what we know about the earth’s climate cycles. Despite what we know about past climate, our activity on the planet is propelling us into a more uncertain climate and weather future. Another reason it should not be taken lightly is because of our now high dependence on the West as a source of livelihood and sustenance. The Central Valley now grows almost 60 percent of America’s produce, California alone sustains almost 40 million people, and snowpack provides the majority of the state’s annual water supply. Yet we may ill-prepared to handle the impending climatic changes . Our levees and dams are aged and in need of repair, the population continues to grow and has sprawled onto sinking floodplains, and “water policy in the West has made [water] a resource that is easy to seize and exploit by those with the power and will to do so” (212). The authors propose several solutions to preparing for a less certain climate future characterized by drier conditions interceded by acute flooding. Some of these include acknowledging and more seriously adopting the perspective that water scarcity is a way of life in the West, decreasing our water footprint (by consuming less water-intensive food like beef and dairy and getting rid of lawns and landscapes), increasing water prices using a tiered by-consumption approach, limiting population growth and the controlling the location of residences, restoring environmental flows, and repairing flood infrastructure. I don't perceive their message to be an apocalyptic one, but one that encourages earnest adaptation efforts. What I've presented here is enough to digest and think about, so I'll comment on only one thing the book made me think about: the concept of time. What was “long ago” versus what was “recent” is relative, and changes both in the eye of the beholder and based on the issue in which time is related. My grandmother is 93 years old. She was alive when “Thirst” was produced, when the West's largest aqueducts were built, and just barely missed the epic valley floods of the late 1800s. What seems like distant past to me is really not. The fact that I know people born almost one hundred years ago, and that when I was a child, I knew great-grandparents that were around before the modern West even existed, illustrates how much things——like climate and resource use——can change in a single lifetime. Our bounded cognition, developmental process, and experience evolving as self-preserving and self-centered individuals, however, limit our ability to comprehend the importance of the ‘past’ and cause us to overvalue and prioritize the present. What might we do to overcome these human limitations to perceiving time and to increase our propensity to adapt? I’m not entirely sure, but here are several considerations that come to mind. First, when we hear projections on what the climate and environment will be like in years to come, we should think about them in relation to our own life's timeline (e.g., in 2070, I’ll be in my eighties and my grandchildren, if I have them, might be entering highschool). Doing so might help contextualize the future in a way that makes it more valuable to us. Second, we should better integrate principles of water conservation and water recycling into classroom curricula in the West. Promoting adaptive strategies in children should help to cement habits and perspectives of resource responsibility early on. Third, modern humans——Westerners in particular——should probably develop a deeper respect and appreciation for the natural world and our place in it. It's possible that our contemporary lifestyles have created a potentially dangerous ignorance of our dependence on earth's resources, including its climate. We need to reconnect. Finally, we should better understand the ambitions, incentives, and constraints of the decision-makers——political and otherwise——that make choices about how our resources are governed and used. This is an area that many social scientists, myself included, are trying to figure out. More on that later. |

ArchivesCategories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed